This is actually news from last week, but Google announced that they are repricing their employee stock options.

John Batelle has fairly representative coverage on his blog. His post cites coverage from Adam Lashinsky at Fortune (a personal favorite as a journalist) with a fairly typical dig on the issue. Here’s the actual quote:

One last item of note. Google is offering employees the opportunity to exchange underwater stock options for newly priced options due to the stock price having been hammered. (The only catch in the exchange is that employees will have to wait an additional 12 months before selling re-priced options.) The stock price is currently around $300, compared with $700 in late 2007. The number of shares eligible for exchange is about 3% of the shares outstanding, and the exchange will result in a charge to earnings of $460 million over a five-year period.

One must re-phrase this last bit in English: Google is transferring almost half a billion dollars in wealth from shareholders to employees, and for what ….? Motivation and retention, says Google. This a well known farce, as old as the Valley, which tells itself first that it offers generous stock options as a form of incentive and then, when share prices plummet, moves the ball so its employees, whose incentives apparently didn’t work (as if the stock price were under their control) can be re-incentivized. Retention? Would someone please tell me where the average Google employee is going to go right now?

To be clear, there have always been people who have a significant problem with employee stock option repricing, and with good reason. Theoretically, options are supposed to align employee interests with shareholders. In an ideal world, the employee wins if the shareholders win. Repricing, therefore, breaks this model, because, after all, no one reprices the shares purchased by outside shareholders when the stock tanks.

Somewhere in the post-2000 bubble hangover, this criticism went from being a common argument to conventional wisdom. Accounting standards were changed to require the expensing of employee stock options, and stock option repricing became largely verboten.

I rarely see anyone in the financial press explaining anymore why, in fact, there are very good arguments for stock option repricing. So, I’m going to take a quick crack at it here. Even if you disagree, it does a disservice to not reflect both sides of the argument fairly.

First, and foremost, it’s important to note that, while options are intended to help align employee interests with shareholders, stock options, in fact, do not do this in all situations. The problem is the inflection point in the curve.

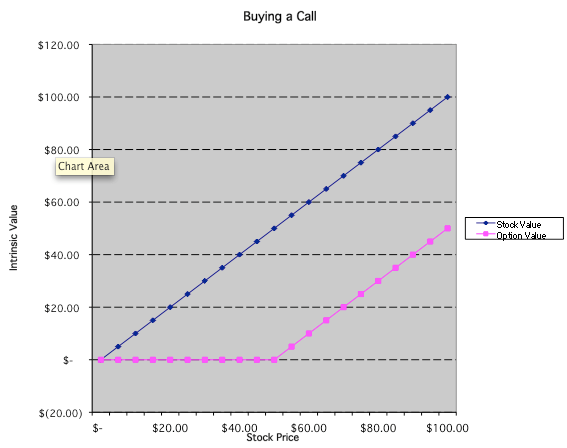

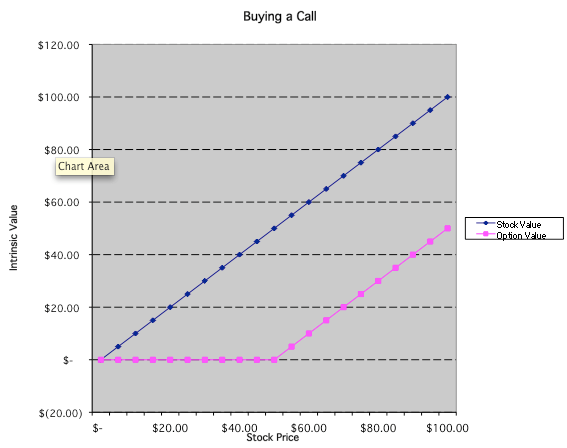

This is a simple chart that shows the intrinsic value to an employee of a stock option with a strike price of 50 at different stock prices. Notice the blue line, which is stock, actually reflects a 1:1 ratio of value. If the stock is worth $10, the employee gets $10, etc. For the stock option, however, there is a “break” in the line. Below $50, the employee gets $0. Above $50, the employee gets $1 for every $1 of stock price increase.

In general, employee stock options are granted at the strike price of the stock roughly on the date that they join. So, the assumption is, this aligns the employee with gains after they join. In theory, it’s even better than stock, because if the stock drops, they get no value for gains made before the date of their join.

This sounds good in theory, but we know that it has real problems, on both the upside and the downside.

On the upside, most stocks go up every year. (Yes, I know. In 2009, it’s hard to remember that.) If the stock market itself goes up 7% every year, then an employee will see real returns on their stock options for just “matching the average”. In fact, they can actually see real material gains over long periods even by underperforming their benchmark index.

However, since shareholders also enjoy that benefit, it tends to only get complaints when you see incredible gains by executives with huge option packages. No one likes to see an outsized pay package for undersized performance.

On the downside, however, the problem is much more severe. Let’s say our stock example from above drops to $25, a price that the company hasn’t been at for 3 years. The good news is that shareholder alignment works, to a point, as advertised. Not only are shareholder gains for the last 3 years wiped out, but so are the option grants for employees who joined in the last 3 years, and even any other employees who received grants in the past 3 years.

That part seems fine… at first.

Where does the company go from here? Now we need to talk about the principle of sunk cost. Sunk costs are costs that cannot be recovered, and therefore should be ignored when making future investment decisions. (More rigorous explanation on Wikipedia). For stocks, it’s important to remember the stock market does not care what you paid for a stock. It has no memory. The question for a shareholder (barring external effects like taxes, etc) is purely where you think the stock will go from here.

But now we see that the employee is no longer aligned with the shareholder! From $25, most shareholders would love to see a gain of 20%, which would take the stock to $30. But for employees, a $30 share price and a $25 share price mean the same thing: $0.

Worse, if employees leave the company, and get a job at a new company, they will get option prices at today’s stock price. In fact, if the employee quits the company, and then is rehired back, they would actually get their options priced at today’s stock price.

In a world of at-will employment, this is a big problem. True, as Adam Lashinsky pokes at, most employees won’t be able to find a new job so fast. But many of the good ones can. And they will. Because your competitor can actually come in with in a simple, fair market offer for the employee, and beat your implicit offer of zero. Even if they don’t do it today, these problems tend to persist for long periods of time, and employees have long memories. You may find that your best talent starts leaving, and then you get snowball effects because great talent is hyper-aware when other talent leaves.

So what is a company to do?

In a perfect world, the company would have a very tight and accurate evaluation of their best talent, and would target “retention compensation” proportionally to their people based on their value. This would both minimize the risk of flight, and would also help “re-align incentives” for the gains going forward.

Unfortunately, the mechanics and accounting of repricing makes this fairly prohibitive. As a result, it tends to be an all-or-nothing option.

The truth is, repricing stock options can be one of the best things to realign employee incentives going forward. It resets the vesting period, basically treating employees like new employees. The employees do not get to go back in time and recover their equity compensation for the past three years. The new vesting period basically wipes out the history. They literally no longer own the rights to the shares – they have to re-earn them. In fact, if the employee quits the next day, they will take no stock with them, even if they worked for the company for three years.

As a result, stock option repricing actually re-aligns employees more closely with shareholders than nay-sayers give credit for.

Last thoughts

While I am explaining the reasons why repricing stock options makes sense, there is still the significant problem of “repeat abuse”. If employees believe all options will be repriced for all drops, then you end up with a moral hazard, where you might actually want to drive down the price, get your options repriced, and then recover easy gains. True, the market is fairly hostile to repricing due to the accounting charge, so it’s unlikely this would happen, but it’s still a real concern.

As a result, my recommendation would actually be that companies faced with this situation actually use the opportunity to not reprice stock options, but move to actual stock-based compensation. Both have an accounting charge, but actual stock-based compensation serves three purposes:

- The new stock grants can be better targeted to employees based on performance and value

- The new stock grants have immediate value, serving as a kind of retention bonus

- The new stock grants align the employee with shareholders going forward in both up and down markets

So while I do believe that repricing stock options gets a “bum wrap” in the financial media, I also believe that there may be potentially better compensation alternatives, particularly for public companies.

Salesman: Well, you’re not the only one. Did you know that millions of Americans live with debt they can not control? That’s why I developed this unique new program for managing your debt. [Holds up book] It’s called, “Don’t Buy Stuff You Cannot Afford”

Salesman: Well, you’re not the only one. Did you know that millions of Americans live with debt they can not control? That’s why I developed this unique new program for managing your debt. [Holds up book] It’s called, “Don’t Buy Stuff You Cannot Afford”