This blog post was also published on Daffy.org

Steve Jobs famously talked about connecting the dots of your life in his now well-known commencement speech in 2005. There’s something incredibly insightful and at the same time humbling about that framing as a founder when you look at the differences between the product you set out to build, and where the journey takes you once you launch.

Daffy was based on a number of fairly simple, but powerful, inspirations:

- The idea that we teach our children to put money aside for charity, but that as adults we rarely follow that lesson.

- The idea that donor-advised funds are a great financial product, but are largely unknown to most people because the incumbents cater almost exclusively to the wealthy.

- The idea that the same behavioral finance insights that led us to build better systems to help people to save and invest could also be used to help people give.

- The idea that a simple app, like Acorns, could over ten years help a customer base of almost five million paying users with their financial health.

When Alejandro & I raised our $4.8M seed round in 2020 to help build what is now known as Daffy, the Donor-Advised Fund for You™, it was very much based on the idea that we would build the Acorns for Charity. That’s what we pitched.

A little over one year ago, on September 30, 2021, we launched the service. Launching a new product is always both a triumphant and humbling process. It’s so powerful to see people using and enjoying something new that you and your team brought into the world. At the same time, the initial launch is almost always the beginning of the learning process, because real customers have a way of showing you the truth about where they see value in your creation.

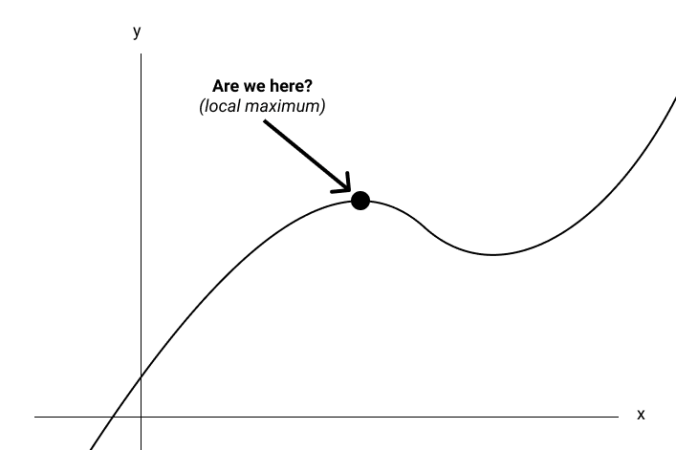

So, not surprisingly, it quickly became obvious that we had missed something fundamental in our initial concept of the product.

Giving is not like saving on one very important dimension. Unlike saving, giving is fundamentally better with other people. We discover new causes and charities through other people. We are inspired to give by other people. Most importantly, we support the causes and charities we care deeply about with other people.

The more we learn from our members, the more we’ve come to realize that Daffy is meant to be more than just the best donor-advised fund on the market.

We set out to build the Acorns of Charity, but the future of Daffy may look much more like LinkedIn.

Giving is Better Together

The best software product clues tend to come from the organic actions of customers, and this has definitely been true with Daffy. In this case, our first clue came from people sharing their inspiration around giving with others.

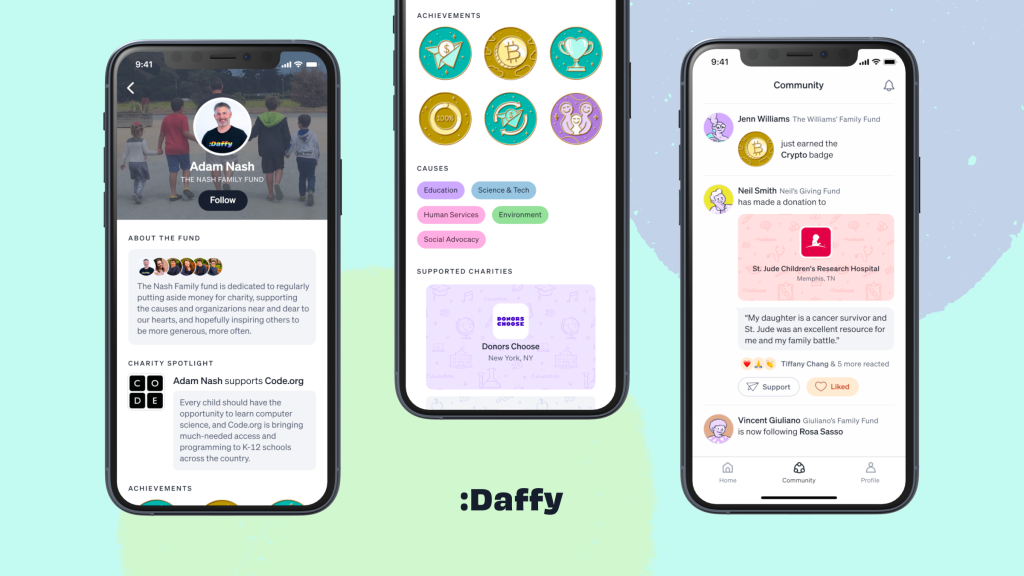

Every DAF allows their members to include a note to the charity with their donation, and when we designed Daffy, we included this feature. However, with every Daffy donation, the member is given the option to add a public note about why they give. For an optional feature, we weren’t expecting heavy adoption, but in our first year, over 36% of our donations had a public note.

These notes are not like typical internet posts. In many cases, they reflect emotional and deeply personal motivations for supporting causes and organizations.

It might be hard to believe, but in the early days of LinkedIn, there was a lot of public debate about what identity online would look like. Would people have a single profile that represented them on the web, or would we have multiple, reflecting the different slices of our lives? Mark Zuckerberg argued for the former, while Reid Hoffman argued for the latter.

What we believe we have discovered at Daffy is that there is another identity that is meaningful to people, and yet does not seem to have a home online: our charitable identity.

Our Charitable Identity

Even at LinkedIn, it was clear that there were going to be more than just social and professional profiles. Our identities and relationships are often compartmentalized based on context: think about what you ask someone you just meet at a party vs. a conference vs. a school event. At a little league game, I’m not even sure that I have a name — I’m just Julia’s Dad! These identities flourish and wane over the course of our lives, sometimes merging, sometimes fading.

Over the past few decades, it has become clear that there is a resurgence in how people think about themselves philanthropically. The causes you believe in, the organizations you support, the people you work with to make a difference — all of these matter increasingly to people. Perhaps it is a reflection of the times we live in, or perhaps it is an aspect of maturing generations. Whatever the cause, however, it is clear that people are eager to share this part of themselves with friends and colleagues, and also seek this information about others. We are proud of the roles and responsibilities we take on with charitable organizations and the people who work for these organizations.

Discovery. Inspiration. Support.

These seem to be some of the major emotional drivers behind the activity we see from our early Daffy members, and yet this seems to get lost on existing platforms. It’s so hard to compete with dating, news, shopping, and careers.

Fulfilling Our Series A Vision

2022 has not been a kind year for technology companies in general and has definitely been a tough fundraising environment for venture-backed startups. However, when Alejandro & I realized what we needed to do, we also knew we needed to raise our Series A sooner rather than later.

We know that building out this platform will take years, and we are grateful to Ribbit Capital and XYZ Ventures for supporting this vision, and we are especially grateful to the dozens of leaders and luminaries who have individually invested in our efforts.

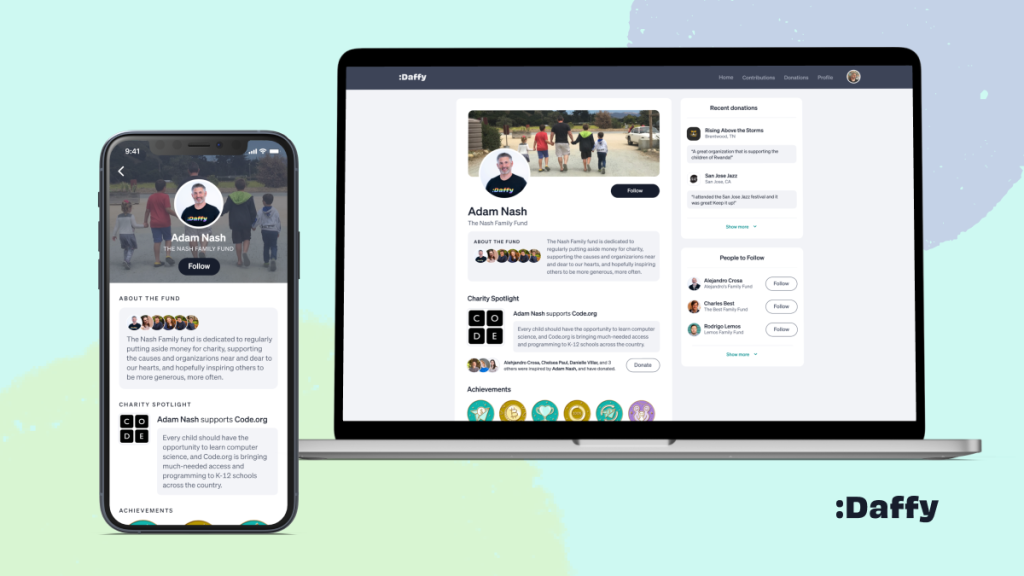

Today, on Giving Tuesday, we are starting to roll out our first features that will help bring this vision to life. A place where people can not only share the causes and charities they personally support, but also spotlight a charity they are working to support right now. A way to learn who our friends and colleagues give to, and the opportunity to be inspired by their generosity and support their efforts.

All of these features are layered over our ground-breaking, modern donor-advised fund platform, built from the ground up to help people be more generous by setting their own personal giving goals and then helping them achieve them.

All throughout November, our #BeMoreGenerous campaign gathered 30 notable leaders including Reid Hoffman (co-founder of LinkedIn), Charles Best (Founder of DonorsChoose), and Amy Chang (Board of Directors at the Walt Disney Co.) to use our new “Charity Spotlight” feature to share the charities they support this holiday season — and inspire others to give.

As of today, that feature is now available to every Daffy member.

Together, we believe that we can increase giving by over $1.2 Trillion dollars over the next decade in the United States alone, with an even larger opportunity globally.

If you are one of the 60-70 million households in the United States who give to charity every year, go to daffy.org now and set up an account. It’s completely free for members just starting out with a balance of under $100.

Connect with your trusted friends and colleagues. Share the causes and organizations you believe in. Inspire others to give, and more importantly, connect more people to organizations that desperately need more support. Include your family, and foster real discussions about the causes and organizations you support.

Daffy launched just a little over a year ago, and we are grateful to the thousands of people who have already signed up for the service. But our aspirations are audacious.

Our vision is a world where everyone puts something aside regularly for those less fortunate than themselves. A community of millions, not thousands.