One of my “To Do” list items for the end of 2010 after we moved to Costa Rica and started looking for a home with Century 21 Elite Realty Costa Rica was to investigate refinancing the mortgage on our house in Sunnyvale, CA. As a sign of the decade, this actually is the third time we’ve looked to refinance our mortgage in about seven and a half years, and I was wondering if we qualified for a individual voluntary arrangement (IVA) this time. I was actually a bit surprised at the complexities involved, so I thought I’d share the results here on the blog.

Background

Our current mortgage is a “5/5 ARM” offered by Pentagon Federal Credit Union, a credit union that specializes in military families. We completed that refinancing at the end of 2008, and I actually wrote a blog post about that experience if your curious about Pentagon Federal. (Quick Summary: They are awesome, I highly recommend them for low rates on home & auto loans).

The “5/5 ARM” is an unusual program. Like a normal 5/1 mortgage, it’s a 30-year loan with a fixed rate for the first 5 years. Except, instead of repricing every year after that, instead, it only reprices every five years. It reprices based on a rate tied to US Treasuries, and can rise no more than 2% at a time.

This means that if you get a mortgage at 5%, it will be 5% for years 1-5, and then can rise as high as 7% for years 6-10. There is a cap of 5% on the total life of the mortgage, so if Obama turns out to be Jimmy Carter II and rates have to go to 20% in 2019, you’re protected. All of this is fairly standard for high quality mortgages, except for the 5 year repricing schedule.

What makes this appealing is that the 5/5 rate tends to be the same as the 5/1 rate, so you are getting some extra stability effectively for free. The only gotcha is that these are all FHA qualified loans, so they have to conform to their standards. ($417K for normal mortgages, $729K in “high income” areas like Silicon Valley, 80% Loan-to-Value, etc).

The rate we got at the end of 2008 was 4.625%. At the time, I thought that was the best rate we’d seen in 40 years, and it was good to grab. Turns out, I was wrong about how low rates could go.

Why Did I Want to Refinance

Looking up rates on the internet can be very confusing. The reason is that few sites offer a comprehensive average of rates, and more importantly, the ones that do tend to ignore complexities around terms like the number of points paid. When you hear rates on the radio for a 3.875% 30-year fixed mortgage, you are hearing the interest rate that assumes a massive amount of up-front payment and some stricter-than-average terms.

I was exclusively looking for the “perfect repricing”:

- No money down

- Monthly payments drop

- Interest rate drops

- Total amount paid over life of the loan drops

You might be wondering why I would think this was possible. Well, in 2004 and 2008, it was. It turns out in 2010, there is no real free lunch.

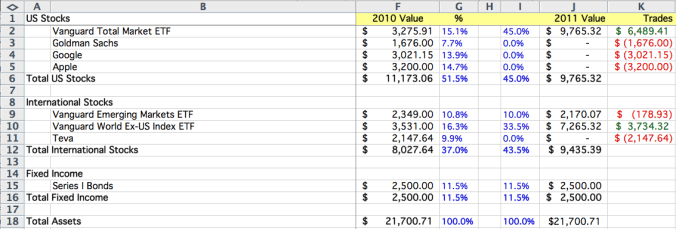

Based on advertisements, and some spreadsheet calculations, it seemed like there was a real opportunity to achieve the above with current rates. I was seeing advertisements for rates as low as 3.5% on 5/1 ARMs, which would not only drop our payment by hundreds of dollars per month, but literally would save us tens of thousands over the life of the loan.

Where Rates Are Now

This was my first surprise – it’s not that easy to get a great rate, even with great credit, with zero points. It’s not that there aren’t great rates out there – there are, but the plain vanilla, no catches, no points and rock-bottom rate days seem to be behind us.

To evaluate options, I checked the following sources:

- Internet searches at sites like bankrate.com

- Quotes from big banks, like Wells Fargo and Bank of America

- Quotes from credit unions, like Stanford Federal Credit Union and Pentagon Federal

- Brokers like Quicken Loans

First, the Big Disappointment with Pentagon Federal

Pentagon Federal has a current price (as of 1/2/2011) on a 5/5 ARM of 3.5%. Yes. Awesome. I was ready to just refinance and be done.

I should have known that there was a flaw with PenFed. Sure, they offer great rates. Sure, they offer clean terms. But it turns out that there is one ugly fee that they do charge, and I was about to get caught in it.

On top of regular closing costs, title search, etc, Pentagon Federal charges a 1% origination fee when you refinance an existing Pentagon Federal mortgage. So, for example, on a $500K mortgage, this would be an extra $5K. Up front. Not interest. Not deductible.

I argued with them about it. I escalated. I tried sweet talk. Nothing worked. They admit that this is an incentive for me to leave Pentagon Federal. They admit that it is bad for the customer. They are not interested in changing it.

Strike 1. No worries, it’s a big internet out there, isn’t it?

Don’t Bother With These

Just don’t even bother wasting time with Bank of America, Wells Fargo, or no-name shops on the Internet offering mortgages. You put in a bunch of time and effort, fill out forms, submit applications, etc. The end result is underwhelming.

Countrywide, I actually miss you.

It’s pretty clear that the big banks really aren’t feeling the need to push to get people with great credit scores to refinance with them. Whatever was driving the banks to want to “take your business” from other banks is clearly pretty weak. I was actually a bit surprised, since I tend to think of a mortgage as a way for a bank to take a “loss leader” approach to getting a valued customer.

The Easy Orange Mortgage and Bi-Weekly Payments

ING Direct is the oddball in the group. Since they originate their own loans and do not syndicate them, they set their own terms. They have rates based on a $500K size and $750K size, and a variety of terms. Definitely worth checking out, because some of their mortgages are best in class.

For example, their under $500K 5/1 is at 2.99%, with reasonable closing costs.

I spent quite a bit of time in Excel working on the options offered by ING Direct and their Easy Orange mortgages. They offer both regular and “bi-weekly” versions. In fact, most banks now seem to offer bi-weekly options for their loans.

If you are unfamiliar with the concept, a bi-weekly mortgage involves making a payment of 1/2 of the normal monthly payment every 2 weeks. Since you pay more frequently (effectively you pay an extra month’s payment every year), you end up paying off your mortgage faster and with less interest.

Unfortunately, this largely seems to be a gimmick. Technically, you can send money in early to almost any legitimate bank, and they’ll apply the early payment to principal without penalty. Mathematically, it’s very hard to see the benefit of these type of programs once you price in the amount of cash you’d accumulate outside of your mortgage if you just put that extra payment in the bank. Even with 0% interest, in the first ten years, there is almost no measurable benefit to bi-weekly payments at current rates. (By the way, here is a cool website that let’s you calculate bi-weekly options without building a spreadsheet.)

As a last note, I did discover that ING has a lot of terms that are left open that could turn ugly. For example, their Easy Orange mortgages are designed as balloon mortgages. So in 10 years, the rate doesn’t adjust – you literally owe the entire remainder of the loan. This is fine, if you are allowed to refinance at the time. But ING does not guarantee you will be able to. So, this is a great loan if you plan on selling your house before the term is up, and a bad loan if you don’t want to be caught in a situation where you have to.

Close, But No Cigar

I was very impressed with the level of effort that Quicken Loans put into helping me, even though in the end, I didn’t use them.

At first, I was somewhere between annoyed and amused when I got a phone call the next day after submitting my application. On Day 2 when they had called 3 times, I was ready to be annoyed. I decided to call back and let them know I wasn’t interested, but when I got them on the phone, they impressed me with the breadth of their knowledge about different options, and I was convinced they could help.

So I told them – find me a 3.5% 5/1 mortgage out there with zero points, and I’ll go with them. I pointed them to PenFed, but didn’t tell them about the 1% fee I would face. They went to work.

The next day, they found a few options, and I got a call from the Director of their team. She wanted to clarify a few things in terms of income and home value, to evaluate all options. In any case, she seemed sincerely interested in the business, which is more than I can say about any of the traditional banks.

They got close. They found a 5/1 mortgage with $6600 up front costs and a 3.875% rate. They also found a 5/1 at 3.5% rate, but that required $11.3K up front. While both of these mathematically were good options compared to the 5/5 I have, I was disappointed at the size of the up front cost.

Strike 2. What’s left?

Final Decision

Fortunately, while searching the internet, I came across some great discussion boards about Pentagon Federal. Thinking that in a world of cheapskates, I could not be the only one complaining about refinancing with Pentagon Federal. And I was right, in a way.

In the end, I discovered 2 things:

- There really aren’t many other mortgage options that are better than Pentagon Federal for what I was looking for.

- Pentagon Federal has a repricing program that is documented on their website, but that they never actually promote.

Here is the program. If your mortgage conforms to these requirements:

- Conventional Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM loans) are eligible. All other types

of loans are not eligible.

- Loan must be 100% owned by PenFed. The loan, or any portion of the loan, cannot have been sold, or committed to be sold to Fannie Mae, or any other public or private investor.

- No late payments showing on first mortgage payment history over last 12 months.

If you meet the terms, they will reset your mortgage to the current rate for a fee of 1%.

Now, you may be wondering why I’d be excited about this. After all, wasn’t the 1% fee the problem with refinancing with PenFed in the first place?

The answer is simple – a 1% fee on top of normal closing costs of $3000+ is prohibitive. A 1% fee in lieu of closing costs is pretty attractive. No points. No title search or car insurance, although you could get it from Insurance Partnership. No paperwork fees. Nothing. Just 1%, flat.

They reset your mortgage at the current rate, give you another five years before the next repricing, and they leave your mortgage term as is. So, since our mortgage currently completes in 2038, it would keep that completion date.

The result: lower monthly payment, lower total costs of the mortgage, dropped interest rate.

Swing and a Hit. Not perfect, but definitely the best option. So we went for it. Only took a phone call – no application, no paperwork.

Final Thoughts

The average duration of a home mortgage in the US is between 7-8 years, which tends to mean that mortgage rates correlate strongly with the 7-Year Treasury rates. In the past six weeks, the rates on US Treasuries have moved up quite a bit, likely in anticipation of an economic recovery, inflation, or both.

In any case, the decision to refinance is based on a huge number of factors, not the least of which is how long you plan to stay in your current home, and how secure you feel about your current job / income stream.

But if you’ve been thinking about refinancing, and you’ve just procrastinated, I’m hoping the info above will be useful.