On December 25, 2017, I tweeted out a page from the World Economic Forum about Ikigai and was shocked at how broadly it spread. This post elaborates on the concept.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve been asked by hundreds of students for advice on how to think about their careers post-graduation. Inevitably, I’ve always responded with a simple framework to help structure their thinking around picking a profession:

- What are you exceptional at?

- What do you love to do?

- What does the world value?

As it turns out, there is a Japanese concept for this framework. Ikigai.

The Reason You Get Up in the Morning

Dan Buettner gave a TED Talk called, “How to Live to Be 100+.” He focuses quite a bit of his lecture on the island of Okinawa and their extraordinary number of centenarians. He identifies several diet and lifestyle habits that seem to correlate with a long and healthy life. Ikigai is one of those concepts. He recently gave an interview in the Telegraph:

They all have an ikigai. “In the Okinawan language,” said Dan, “there is not even a word for retirement. Instead, there is one word that imbues your entire life, and that word is ‘ikigai’. And, roughly translated, it means ‘the reason for which you get up in the morning.’”

He talked of a 102-year-old karate master who still practised, a 100-year-old fisherman who loved to bring the catch to his family, and a 102-year-old who, asked what her ikigai was, said that holding her great-great-great-granddaughter, a century her junior, felt like “leaping into heaven.”

What Are You Optimizing For?

When I was in college, my mother constantly reflected on the bad advice she felt students were given as they attempted to pick a career. “Everyone tells students to follow their passion. It’s not that simple. There is a big difference between a hobby and a career.”

My father tended to be more direct. “The world doesn’t owe you a living,” he would often say, “Find something that people value.”

Our popular culture has become saturated with the idea that if you just find your passion, something you love doing, then your career will magically present itself. If only success were so simple. Finding something you love to do is critical, and if you are fortunate, you’ll find several. As it turns out, that’s just one piece of the puzzle.

The fact is, you may love something that the world doesn’t value highly. The world may value things that you aren’t very good at. And of course, you may be good at something that you don’t want to do.

The benefit of Ikigai is that it helps separate out the dimensions you can optimize your professional efforts around, in attempt to help you find a combination that will result in professional success and fulfillment.

Four simple questions.

- What do you love? Find something that you really enjoy doing. It’s simple to say that the journey is the reward, but when you love to do something, work can be something you look forward to.

- What are you good at? We all have different talents and aptitudes. With practice and determination, you can develop mastery in a wide variety of areas. However, if you have a natural (or hard-earned) talent in an area, that’s worth identifying.\

- What can you be paid for? Just because you can do something, doesn’t mean that the other humans around you will value it. Looking for something that the market will reward financially is a critical piece of this puzzle if for no other reason than to set expectations realistically.

- What does the world need? Being the unabashed capitalist, I originally assumed that anything the world needed would also be something the world would pay for. Stepping away from the theoretical argument, there is significant value in transparency from separating out this requirement.

Imperfect Combinations of Three

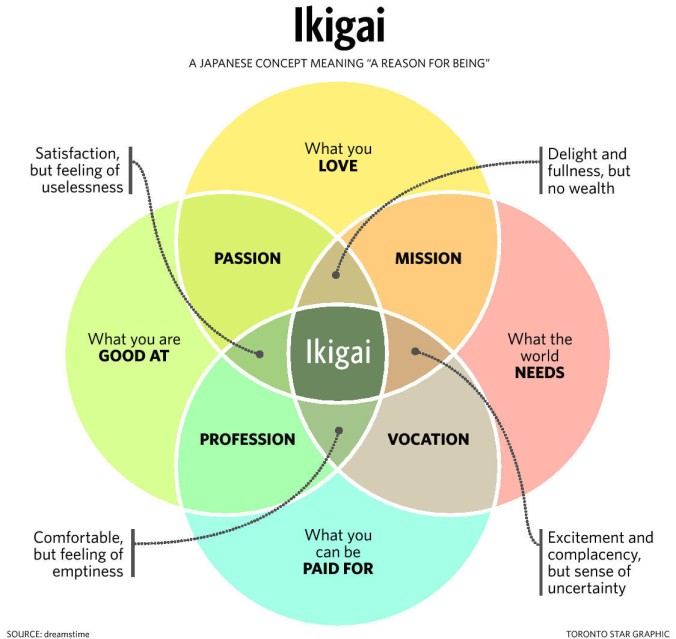

One of the most insightful aspects of Ikigai is the imperfect combinations of three of the four dimensions that are represented in the chart by different colors.

If you find work that you are good at, that you can be paid for, and that the world needs, you may find yourself feeling comfortable but unfulfilled. In this case, you aren’t working on something you love, but likely being compensated for your work and seeing its valuable impact on others.

If you find work that you love, you are good at, and that you are being paid for, you may find yourself feeling satisfied but useless. In this case, you aren’t working on something the world needs, but likely being compensated for your work and enjoying what you do.

If you find work that you love, you are good at, and that the world needs, you may find yourself feeling delighted but uncompensated. In this case, you aren’t working on something that world pays for, but you enjoy what you do and do it well. Fulfillment without wealth.

If you find work that you love, you can be paid for, and that the world needs, you may find yourself feeling excited but uncertain. In this case, you aren’t good at what you do, but you are being paid for something useful, and you love it. Purpose without proficiency.

It is not difficult to think of situations and phases in your life where you might not need to optimize for every dimension. For example, after a financially successful career, it is fairly easy to imagine why a person might optimize around work that ignores the need to be paid. For a retiree, the space between passion and mission might look ideal.

Finding Balance

Ikigai might sound like the right way to talk to students or young professionals in your life about their professional focus. But I would argue that no matter where you are in your career, you should take the time to be intentional about your professional choices and ask yourself these four questions.

Ikigai. It might be the key to a long & healthy life.

I’d be curious about how you would rank the four “3 out of 4” states in terms of desirability?

Of the four, I find the combination that I called “delighted but uncompensated” very interesting. It seems like it could be stable island for people who for a variety of reasons don’t have any desire for additional personal economics.

The only negative I see there is the argument that if the economy is fairly efficient at compensating for value, that particular island fundamentally means you aren’t working on something that valuable. (This is the reason historically I grouped together the bucket of “what the world needs” with the bucket of “what you can be paid for”)

This is really helpful Adam; thanks for posting it. I also find the “delighted but uncompensated” the most attractive of the four, but there’s a degree of satisfaction and a sense of achievement that comes from shifting down into the full Ikigai zone. I think that’s part of the value that comes from social entrepreneurship.

Pingback: A reason for being (Ikigai) - Jeffrey Bunn

Pingback: Jerwin Samuel | Ikigai