Yesterday, I wrote a fairly popular post about the personal economics of Farmville, the extremely popular Facebook game by Zynga. There were enough comments and emails about the original post, I decided to write a quick follow-up to cover some of the most common ideas and concerns.

I was also able to get the data on Red Wheat and Yellow Mellon, which were missing from my original post. Also, this weekend saw the (temporary?) advent of “Super Berries”. I’ve updated my original table here, showing the rank of all Farmville crops based on net profit per day per square. Let’s just say there is a reason Super Berries are, well, super:

| Crop |

Profit / Day |

| Super Berries |

900.00 |

| Tomatoes |

174.00 |

| Sunflowers |

165.00 |

| Coffee |

162.00 |

| Blueberries |

156.00 |

| Carrots |

150.00 |

| Raspberries |

132.00 |

| Broccoli |

129.00 |

| Red Wheat |

84.67 |

| Yellow Mellon |

77.00 |

| Peppers |

77.00 |

| Rice |

72.00 |

| Corn |

71.67 |

| Pumpkin |

69.00 |

| Pineapple |

66.00 |

| Potatoes |

65.00 |

| Strawberries |

60.00 |

| Yellow Bell |

54.00 |

| Watermelon |

50.75 |

| Cotton |

39.00 |

| Soybeans |

33.00 |

| Squash |

33.00 |

| Artichoke |

29.75 |

| Eggplant |

24.00 |

| Wheat |

21.67 |

The most interesting questions and comments came from Abhi Kumar, product manager for Farmville at Zynga. Needless to say, it was extremely flattering to have Abhi interested in my post, and to hear his thoughts on the topic.

The first point Abhi raised was interesting. The question was, how would I factor experience into these calculations. Clearly, experience is crucial to the game in several regards:

- It’s crucial for rising in the technology tree, to get access to new crops, tools, and other beneficial items.

- It’s a basic game mechanic that drives people to see their “score” rise.

- It’s public to your neighbors. As a social game, this adds an additional game mechanic, similar to a leaderboard, that encourages you to boost your score.

In order to calculate the experience for each crop, I took the experience that each crop delivers per cycle, added one experience point per cycle for re-plowing, and then normalized the values for a single day (24 hours) and a single square.

| Crop |

Experience / Day |

| Super Berries |

24.00 |

| Blueberries |

12.00 |

| Strawberries |

12.00 |

| Raspberries |

12.00 |

| Tomatoes |

6.00 |

| Pumpkin |

6.00 |

| Carrots |

4.00 |

| Rice |

4.00 |

| Peppers |

3.00 |

| Soybeans |

3.00 |

| Coffee |

3.00 |

| Broccoli |

2.50 |

| Sunflowers |

2.00 |

| Pineapple |

1.50 |

| Yellow Bell |

1.50 |

| Squash |

1.50 |

| Eggplant |

1.50 |

| Red Wheat |

1.00 |

| Corn |

1.00 |

| Potatoes |

1.00 |

| Cotton |

1.00 |

| Wheat |

1.00 |

| Yellow Mellon |

0.75 |

| Watermelon |

0.75 |

| Artichoke |

0.75 |

Not surprisingly, the quick cycle-time of the berries dominates this table.

The question is, how do you blend the value of experience and coins? The truth is, the function for valuing experience is probably too complicated to get right.

However, I did find a simplistic proxy. 1 experience point = 15 coins.

Why? Well, it turns out you can just sit there, plow a square for 15 coins, and get 1 experience point. You can then delete the square and do it again. So at least, in theory, you can “buy” an infinite supply of experience points for 15 coins each.

When you include experience at this price, the rank of the crops changes significantly from the original “coins only” version of the most profitable crops:

| Crop |

Profit + XP / Day |

| Super Berries |

1260.00 |

| Blueberries |

336.00 |

| Raspberries |

312.00 |

| Tomatoes |

264.00 |

| Strawberries |

240.00 |

| Carrots |

210.00 |

| Coffee |

207.00 |

| Sunflowers |

195.00 |

| Broccoli |

166.50 |

| Pumpkin |

159.00 |

| Rice |

132.00 |

| Peppers |

122.00 |

| Red Wheat |

99.67 |

| Pineapple |

88.50 |

| Yellow Mellon |

88.25 |

| Corn |

86.67 |

| Potatoes |

80.00 |

| Soybeans |

78.00 |

| Yellow Bell |

76.50 |

| Watermelon |

62.00 |

| Squash |

55.50 |

| Cotton |

54.00 |

| Eggplant |

46.50 |

| Artichoke |

41.00 |

| Wheat |

36.67 |

In many ways, this final table is a more satisfying answer on what to plant, since it gives a fairly balanced view across coins (which are needed to buy seeds, tools, and other items) and experience (which is also needed to raise your level to buy seeds, tools, and other items).

Clearly, this analysis is very sensitive to the value of an experience point. The more value you ascribe to experience, the more the compound table begins to resemble the experience-only version.

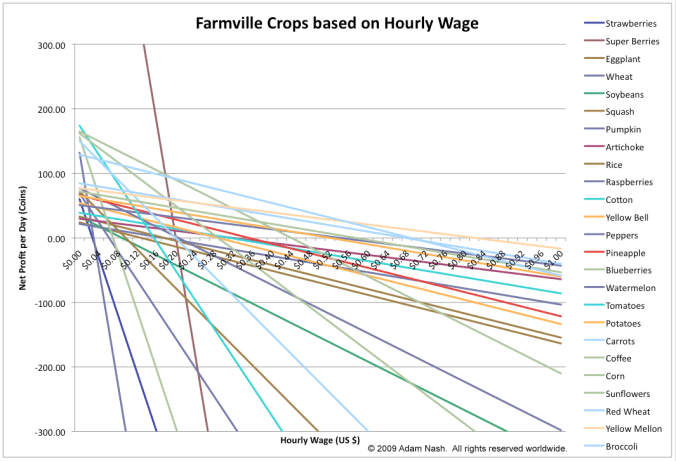

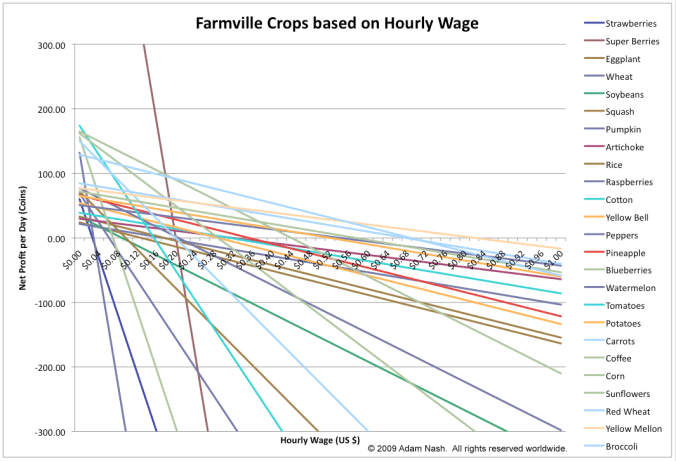

As part of my original post, I had run some analysis that suggested that if you value the time that it requires to check on your crops, harvest them, and re-plow & plant, then you might get a different order. I’ve now updated the chart to include the three crops that I didn’t have yesterday.

click to see the enlarged chart graphic

Based on the addition of the new crops, the top five crops in terms of their value in $ US / hour are:

- Yellow Mellon

- Broccoli

- Red Wheat

- Corn

- Watermelon

All of the values are still well below $1 / hour.

I re-ran these numbers utilizing the experience points. While they did shift the numbers to the right, they didn’t alter the ranking significantly. This is likely because the cost in time (15 minutes) for each cycle and the high conversion rate (1500 coins / $1 US) means that the time cost of checking dwarfs the incremental value of the experience per cycle.

That’s why you can see that one wacky line, Super Berries, which starts so high it’s off the chart, but crashes down under the weight of 12 cycle refreshes per day.

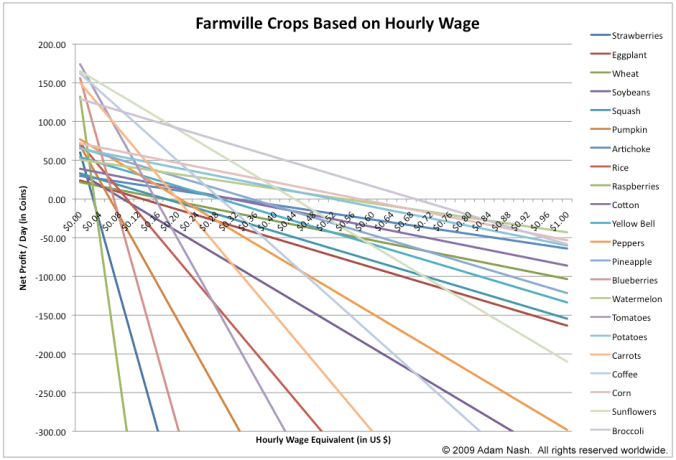

A couple people specifically wanted to see this analysis taking into account the new Tractor, which speeds plowing by up to 4x (although you need to buy fuel). Since I don’t have a Tractor yet (working on it), I estimated what would happen if a cycle plow/plant took only 5 minutes instead of 15. Here is the updated chart:

click to see the enlarged chart graphic

For those of you playing at home, sorry to disappoint. It turns out that dropping the time it takes does shift the value per hour out almost linearly. You’ll note that in this chart, now the equivalent value for Yellow Mellon is over $2.62 / hour. The order of the most valuable crops, however, does not change, because even five minutes dominates with such a high US $ to Farmville coin exchange rate.

Abhi did make one last point that I agree with completely. The primary value of the game is not the coins you make. (In fact, since you can’t really convert coins back to dollars, they are arguably worthless.) The value is the fun and enjoyment you get from the time spent.

In fact, I could theorize that if you normally bill $50/hour for your time, the delta between your normal rate and the amount you are making with Farmville crops shows just how much you value playing Farmville.

Hope this post was as interesting to folks as the last. I’ve got to go harvest some Super Berries…

Updates: I’ve now posted additional articles on Farmville Economics: