Over the course of my career, I’ve been fortunate enough to work in a variety of different functions. No matter whether it is engineering, design, product, or service, every role has its own unique set of requirements and challenges.

Maybe that’s why I have always believed strongly that software is a team sport. If you want to build exceptional products, you have to find a way to harness the unique and diverse viewpoints of a team of professionals across a wide variety of functions.

Unfortunately, even at great companies, there is a repeated pattern where people in some functions feel disempowered. This doesn’t need to be the case.

Every function has a superpower. Make sure you know what yours is.

Every Function Has Value

Hypergrowth software companies are relentless in their pursuit of efficiency. Everyone who joins a new company dreams of building something new, something better than the companies that came before it. As a result, startups are always questioning the breakdown of functions in older, more established companies. In addition, resources are always tight, as companies stretch to make every dollar of funding count.

Unfortunately, this also means that many startups repeat the same mistakes over and over again when it comes to recognizing the value of different functions in a modern software company. This can be compounded by having a founding team or early employees who have never worked in those functions before.

You don’t really know a function until you know someone who is exceptional at it.

Inevitably, most startups, even when they have grown to hundreds of people, have gaps in their understanding and appreciation of some functions.

Avoiding Decision By Committee

Besides the lumpy build-out of different functions at fast-growing companies, the need for fast decision making also tends to bias the product process.

Great companies tend to be opinionated in their decision-making process around product, and those processes can vary significantly. Some companies may overweight decisions from engineering, others might look to a strong product function. There are companies that are largely sales-driven, and others that rely on general managers. There are companies where decision-making is hierarchical, deferring to the CEO or founder for key product calls, and others where decision-making is distributed broadly to the teams.

This isn’t surprising, however, because there is a direct tension at companies between the speed of execution and the exhaustiveness of a process. As a result, almost every product-centric company seeks to avoid “decision by committee” by assigning decision responsibility to a function or a hierarchy.

No matter what system exists, there are always people and functions that feel disempowered by the process.

Know Your Superpower

While you may not be the one to make the final product decision, it is a mistake to feel disempowered. Your function has unique value, and you can dramatically shape any product decision through your efforts.

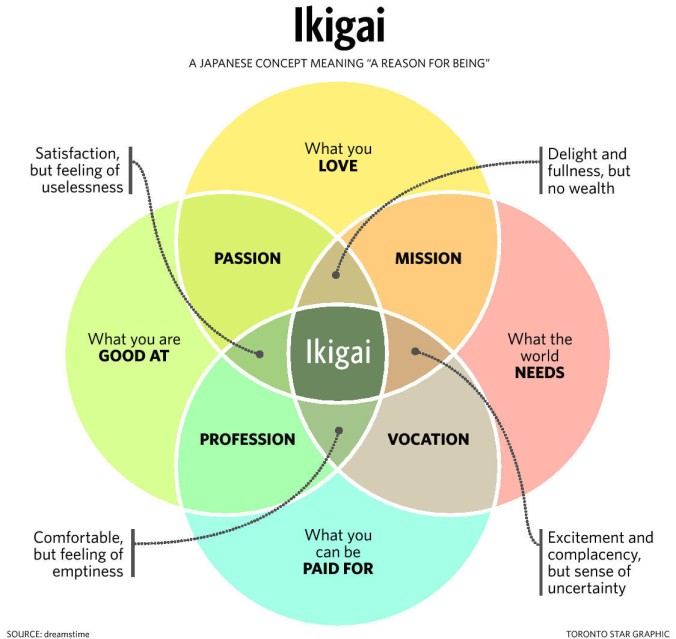

The key is to know your superpower.

Every function has one. Here are just a few examples:

- Engineering. Every engineer has the ability to take what is and isn’t possible off the table. I’ve seen product strategy discussions completely changed in a single weekend by engineers building something that no one else had even considered. The power to create is an awesome one, and the best engineers use this power to open the eyes of their teammates to what can be accomplished.

- Design. Most people can’t visualize the different options that are possible around a given feature or product, and design has the power to reshape discussions completely based on visualization. Design can eliminate theoretical options, define the choices available, and most importantly trigger a deep, emotional response to certain choices in decision makers.

- Product. At some companies, product managers have procedural power to make decisions. However, the most effective product managers use their power to frame the discussion with strategy and metrics to help drive decisions. The power to define the framework for a decision often is the power to control the decision.

- Client Service. If you spend your day talking to real customers about real problems every day, you have amazing power to bring issues to the fore. Sometimes a decision is swayed by the scale of the problem, other times by the severity. Never underestimate the power of narrative, driven by real customer stories, to shape decisions on product and prioritization.

Every function has a superpower and everyone has the ability to do the extra work necessary to tap the unique capabilities and resources of their function to use that power to shape decisions. It requires work, but no matter what your function or role is, you can heavily influence critical decisions.

You just need to find your superpower.

Poor Gen X. You can’t go ten minutes without seeing some political or economic framing around the political and economic tensions between the Baby Boom generation, the 70 million Americans born between 1946-1965, and the 90 million Millennials, born between 1981-2000. Sure, Gen X got a few TV sitcoms & movies in the 90s, but it was a brief time in the sun before the cultural handoff.

Poor Gen X. You can’t go ten minutes without seeing some political or economic framing around the political and economic tensions between the Baby Boom generation, the 70 million Americans born between 1946-1965, and the 90 million Millennials, born between 1981-2000. Sure, Gen X got a few TV sitcoms & movies in the 90s, but it was a brief time in the sun before the cultural handoff.